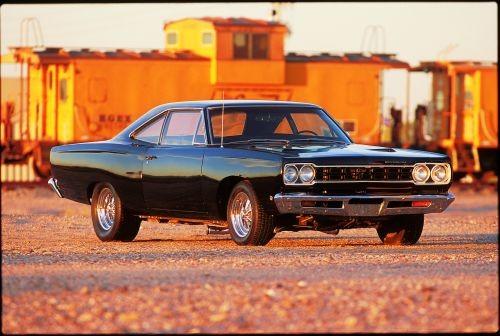

What possesses a person to spend countless hours and thousands of dollars to revive a 36-year-old Mopar? Maybe it reminds her of her younger days, and what fun it can be to go against the grain. Perhaps it’s even therapeutic. In the case of Yvonne McKenzie, who restored our featured 1968 Plymouth Road Runner coupe, it was all of the above.

Youthfulness and fun were baked into every new Road Runner that Plymouth built in 1968, the model’s inaugural year. Up to this point, the performance-car market favored buyers who could spend more than $3,000 on a muscle car; the Road Runner was designed to a lower price point, in both post ($2,896) and hardtop ($3,034) coupes, with a standard exclusive 335hp, 383-cu.in.V-8 and other heavy-duty performance features. Yvonne remembers these cars from when they were new. “I bought my first Road Runner brand new in 1968–it was black over black and silver, with a four-speed. My ex-husband and I both raced it. We sold it in 1975, with only 34,000 miles, for five hundred bucks! I’ve always regretted that,” Yvonne smiles. But her first automotive love never died. Finally in a position to replace the original, she located this Road Runner in New Mexico in the spring of 1999. “It was a shell in primer with no interior,” she explains. “The engine was a bare block, with no starter, alternator, coil, distributor or carburetor–but the body was straight and rust-free.” She paid $300 to have the $1,500 car transported down to her Bermuda Dunes, California, home. With her garage already occupied by her daily-driver 1967 Plymouth Barracuda and the other collectible cars she and her husband Bob share, the Road Runner was parked outside on ramps. “The bumpers and grille were in the trunk, along with Other Mopar parts that didn’t belong with this car,” Yvonne says. She brought the 383-cu.in. V-8 into the garage and disassembled it, labeling and bagging each nut, bolt and fastener. She brought the block and heads to Indio Motor Machine & Supply in Indio, California, where the block was chemically stripped and bored .030-over, the heads were machined and fitted with hardened valve seats, and the crankshaft was ground ten-thousands, balanced and polished.

While the engine was being worked on, Yvonne sent the bumpers, alternator brackets, dipstick and other small engine parts to Orange County Plating in Orange, California, to be re-chromed. She then turned to the column-shifted three-speed TorqueFlite. “My husband taught automatic transmission rebuilding on the college level,” she adds, “so he walked me through, step-by-step.” Because the case was caked in New Mexico’s red clay, she started cleaning it with a putty knife and worked down to turpentine and a toothbrush, scrubbing until it was spotless. With Bob’s tutoring, Yvonne disassembled the 727, carefully cleaned the gears and replaced the reverse bands, gaskets and clutches with new Mopar parts. She also took this opportunity to sandblast the engine compartment and the car’s undercarriage with her portable 30-lb.-capacity Campbell Hausfeld sandblaster. “It was 110 degrees in Palm Desert during the summer, and you have to wear a total protection suit to sandblast–it was hot even in the early morning and late evening!”

When the machining was finished, Yvonne rolled up her sleeves and went to work in her garage. She masked and painted the bare block with aerosol Mopar Performance engine enamel in Chrysler Turquoise, and carefully assembled the engine with new Mopar pistons, rings, valves, bearings and connecting rods; for stronger performance, she installed a Mopar Performance “Purple Shaft” camshaft with .280 degrees of duration and .474 of lift. “I designed the fuel system after talking with Bob Mazzolini, owner of Mazzolihi Racing of Riverside, California–he’s a Mopar engine builder and race car owner,” Yvonne says. “He and his assistant, Jason Mayo, helped me decide how to fit the lines, what brackets to use, and to install a fuel pressure gauge. I originally wanted to use a four-barrel Holley, but Bob said a Carter AFB would be easier to keep in tune, so I chose a Competition Series 625cfm.” She also designed her Road Runner’s exhaust system, which was built by the LNL Transmission Shop in Indio, and consists of Jet-Hot-coated Hedman Headers that flow into three-inch pipes with side-exit dump tubes and rear-exit two-chamber Fl owmaster mufflers. The four-wheel drum brakes also required attention, so she cleaned the drums with the wire wheels on her bench-mounted grinder, installed new shoes and wheel cylinders, and packed in new wheel bearings. She chose to leave the stock front and rear suspensions and factory “open” 3.23-rear axle alone.

Before Yvonne installed the engine and exhaust system, she had to cover the sheetmetal she’d blasted clean. Julian Apostoloff, an automotive paint technician from Cathedral City, came to her house to prime and spray the engine bay with a PPG Deltron DBI interior basecoat paint in “factory pack black.” Yvonne tackled the undercarriage herself with aerosol Kry Ion Tough Rust Primer, topping it with Krylon semi-gloss black paint. She removed the original gas tank and had it cleaned and re-sealed by Jim’s Desert Radiator & Air Conditioning Service in Indlo, the shop that had also refurbished the Road Runner’s radiator; when the tank was finished, she re-fitted it with a new top pad. Prior to the engine being installed, Yvonne ran a new wiring loom that she’d sourced from Year One. “I had the wiring diagrams photocopied and laminated, which made them easier to handle than the bulky manual, and protected them from getting greasy,” she explains. Because her Road Runner arrived with its engine bay nearly bare, she had been attending car shows with her camera in hopes of documenting how 1968-1969 Road Runner engine bays should look. With the engine compartment painted, wired and ready to go, Yvonne, Bob, and two helpers carefully guided the header-equipped engine and transmission into the car, lowering it with a cherry picker. When it was bolted in, she added the 383 pie-pan air cleaner, a chrome alternator, an MSD electronic ignition module, Blaster 2 coil and a lightweight Optima Red Top battery.

“Julian worked on the car for seven weeks,” she explains. “He would walk around the car, sanding, smoothing the metal. He pulled the car into my garage and set up a paint booth using a plastic mesh door screen and special air and paint filters of his own design.” Yvonne carefully masked off all the glass before Julian began painting, using a 5.5hp, 20-gallon compressor and HVLP gun to shoot the car with 3 coats of PPG K 200 acrylic urethane primer. He carefully block-sanded between coats. “He would call me over and draw a yellow circle on the metal,” Yvonne recalls. “He’d tell me to feel it, and I wouldn’t notice anything, but he’d assure me that there was some surface imperfection. When he was done, there wasn’t a ding or mark anywhere on the car.” He sprayed two coats of Deltron 2000 DBC base-coat black paint. Yvonne helped Julian do some wet-sanding before he gave the car a final coat of Deltron DCU 2010 acrylic urethane clear. She installed the taillamps and the clean chrome door handles that she purchased off a donor 1969 Road Runner. When the painting was done and she studied the car, she was smitten by how stark it looked without badges–“It looked so baaad without the decals,” she whistles–that she didn’t use them.

Yvonne spent many hours working on the original dashboard, which carried a factory-fitted tachometer–and like the transmission, the dash was coated with ground-in red clay. “I kept soaking it with Armor-All and lightly scrubbing it with the mildest abrasive pad I could find. It could have easily been ruined, but after a ton of work, it looked as good as new,” she smiles. The gauges, including the aforementioned tach, were overhauled and recalibrated by United Speedometer Service in Riverside before being refitted. Because she purchased the car sans interior, she got a replacement bench seat. Recalling her original 1968 Road Runner, Yvonne designed a custom interior with black and silver leather-faced seats and matching door panels, which were crafted by Liera’s Auto Upholstery in lndio. They installed the recovered front and rear benches over OEM-style black carpet, also attaching the door panels that Yvonne finished with the original chrome trim that she’d polished with her Dremel buffer. She finished the interior with a clean, original steering wheel, which she bought from Mopar Restos in Summerville, Georgia. To round out the nostalgic package, she purchased chrome Cragar SS wheels to match the set on her original car; the modern wheels are 15 x 7 inches front and 15 x 8 inches rear, and they are wrapped in 215/60-15 and 275/60-15 BFG Radial T/As.

Yvonne did add a touch of whimsy to her big black Road Runner–a hand-painted version of the car’s namesake. Pinstriper Mike Schartels freehanded the cartoon bird on the trunklid, perfectly matching the Road Runner tattoo Yvonne got on her calf shortly after buying this car. So what did she put into her first full restoration? “It seems like I spent thou-sands of hours on the car–the first year alone, I worked on it between 8–1 2 hours a day, nearly every day, and I spent about $15,000, not including my labor.” But she gets far more out of the car. “When I started to restore it, I said it was going to be trailered to car shows, but the first time I was able to drive it around the block, I decided it had to be driven; I needed to be able to enjoy it,” she chuckles. “The hay with keeping her spotless– let’s race!”